Learning from 2023 & Breaking Bread with Artists

Nearly four years on after the pandemic, with a growing hyper-individualism created by social media, wars, climate change and nationalism, how can we break bread through artistic discourse?

The phrase "Breaking bread" is deeply rooted in sharing a meal with someone or a group of people, carrying connotations of fellowship, community, and reconciliation. In contemporary art practices, especially in the context of performance art and artist-run supper clubs, this concept can be a potent tool for fostering connections, understanding, and dialogue. In the current climate, where humans are forced to feel like hyper-individualised subjects and more alien than ever, a sense of community, togetherness, and empathy is necessary. Sharing a meal as a gateway to understanding the other and overcoming differences is a common notion. Feeling quite angry, frustrated and hopeless at times, I am writing about this expression, hoping to emphasise the importance of social impact in contemporary art discourse and food as a medium. In this article, I will give examples of international artists who explore this concept of bringing people over a shared meal or activity through their artistic practice.

Laila Gohar - The Art of Hosting

Born in Egypt and having lived and worked in the US for the last decade, artist and food designer Laila Gohar predominantly engages new audiences through food and visual storytelling. Internationally shown in museums and galleries, she is known for her high-profile collaborations and has become a go-to person for fashion, design, gastronomic, and luxury partners. She has commercialised her artistic practice by launching the eponymous label Gohar World and writing regularly in her column with Financial Times. However, no matter what one thinks her training and focus are commercially and product-driven, Laila emphasises collectivity, heritage, and roots through her cooking and food installations. In her latest article, she states, “ It’s becoming clearer to me that while I spent all these years growing further away from my roots, the place I come from has indeed influenced my life’s work. The spirit of hospitality is an integral part of my culture. I once read that the origins of Middle Eastern hospitality stem from the willingness to house and feed rogue desert travellers who passed through town.”1

Vivian Sansour - Palestine Heirloom Seed Library

I first met the artist, storyteller and conservationist Vivian Sansour when she was residing at Delfina Foundation as a part of “Food Politics” in 2019. I was fascinated by her passion for sharing the stories of people who cannot whilst working directly with farmers from her native Palestine and around the world to find and reintroduce threatened crop varieties whilst collecting stories to assert the ownership of seeds by communities.

A culinary historian, enthusiastic cook and columnist, Vivien wants to bring threatened varieties “back to the dinner table to become part of our living culture rather than a relic of the past.” This has led to collaborations with Dan Saladino from the BBC Food Program and internationally acclaimed chefs Anthony Bourdain, Sammi Tamimi and Tara Wigley.

While born in Jerusalem, Vivien was raised in both Beit Jala in Palestine and the US and proudly calls herself a PhD dropout (which I can relate to). What struck me most about Vivien’s practice was how eager she was to tell the stories of Palestinian farmers facing the dangers of agribusiness, corporate seed, land dominance, and political violence, but also making sure they were safeguarded. Today marks 100 days since Israel’s war on Gaza. In the ongoing attacks and killings of over 30,000 civilians, I am not sure even if I can say that Palestinian heirloom seed varieties are under threat; by now, many have gone extinct, and heritage cultivation has been erased. These seeds that have been passed down over the centuries carry in their genes the stories and the spirits of the Palestinian indigenous ancestors. Aside from their cultural significance, these seeds carry options for our future survival as we face climate change and the erosion of agrobiodiversity worldwide. As such, through the Seed Library and its extension Traveling Kitchen by hosting meals and giving lectures, Vivien has been seeking to preserve and promote heritage and threatened seed varieties, traditional Palestinian farming practices, and the cultural stories and identities associated with them.

Laura Wilson - connecting bakeries and galleries through collective memory

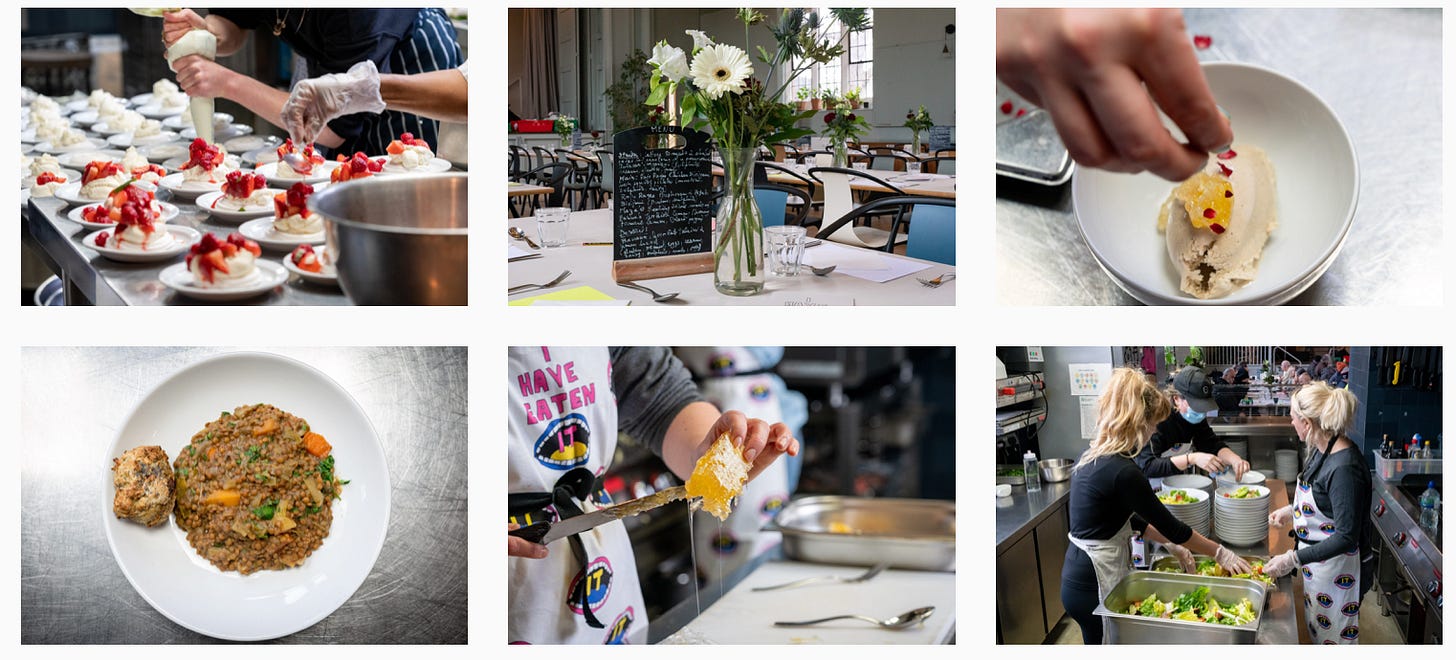

I had the great privilege to collaborate with London-based Northern Irish artist Laura Wilson with Open Space’s Edible Goods iteration titled “I Have Eaten It”. The co-curated project took part as a 4-week kitchen takeover at Refettori Felix, a charity based at St. Cuthbert’s Centre in West London, providing creative experiences around food for vulnerable people. Over this period, we created a tailored weekly meal using seasonal and waste food, with recipes or ingredients contributed by nine international artists. The evolving menu and culinary experience were accompanied by a programme of public events, a fundraising dinner cooked by renowned chef Ramael Scully, and artwork sales, with proceeds going towards Refettorio Felix.

I won’t go into this project much as I want to focus on a specific video work by Laura that inspired me to work with her, especially because she works closely with specialists to develop sculptural and performative works that amplify the relationship between materiality, memory and tacit knowledge.

Commissioned by the 5th Istanbul Design Biennial, the film “Empathy Revisited: Designs for More than One” explores and discusses collective memory, embodied knowledge and the passing on of traditions, recipes and gestures through the preparation of a recipe, punctuated by clips from video works and interviews with my collaborators. In this video, Laura is joined by Turkish chef Irem Aksu, where we discuss the word ‘veda’ and cook a collaborative dish – Trained on Veda Almond Tarator with Baked Hake and Samphire Tempura – inspired by Veda bread and our respective heritages: Northern Irish and Turkish. Laura is also joined via video call by former collaborators, choreographer Lucy Suggate and archaeologist Dr Melanie Giles, to discuss the traces left on our bodies and muscle memory. By literally “breaking bread” through collaboration and sharing a recipe, Laura emphasises the importance and value of collectivity through food.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: participatory installations and communal meals

From all of the examples, Rirkrit Tiravanja may be an obvious one. Still, his practice has been pivotal in bringing social impact and communal eating to contemporary art. Tiravanija is best known for his intimate, participatory installations that revolve around personal and shared communal traditions, such as cooking Thai meals, that are, in the words of curator Rochelle Steiner, “fundamentally about bringing people together.”2 One of his famous works, "Untitled (Free)," transformed a gallery space into a kitchen where he cooked and served rice and Thai curry to visitors. His work breaks down the barriers between artist and audience, inviting participants to share a meal and dialogue within the art space. Through his many shared meals and gatherings, Tiravanija has advocated for a sense of community and solidarity whether you like his work. This sense of unity has been crucial in the face of climate change or inequality. Shared meals can be a starting point for collective action, where individuals feel empowered to work together towards common goals.

Even though all of these examples I provided might not solve deep-seated issues overnight, in all these ways, breaking bread can be a powerful tool for addressing and making space for discussions about serious global issues.

Thank you for reading; if you want to support my writing and research, please subscribe and/or donate above.

Gohar, Laila. “Dishes from My Egyptian Childhood.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 5 Jan. 2024, www.ft.com/content/c8711a2d-f431-4bfc-b4aa-40a0efa21efb.

Quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “Shall We Dance?,” The New Yorker , 2005.