With my new part-time Masters degree in Anthropology of Food and new learnings I decided to examine the role of cookbook authors and their relationship to Anthropologists if any. Having published and co-written a cookbook with artist Inés Neto dos Santos titled Tender Touches, I have been always interested in the story-telling aspect of the cookbook and how it becomes more than a coffee-table book itself. How can we as cookbook authors or creatives publish something relevant that is not necessarily catered to mass audience and create something unique that both provides accessible recipes and added information?

As internet users increasingly migrated to video-based social media platforms, how they engage with cooking recipes and methods has significantly changed. These platforms prioritise short, visually appealing content over deeper cultural understanding, with cultural context lost and authenticity questionable. The "TikTok recipe" phenomenon reduces complex dishes to 60-second videos focusing on aesthetic appeal rather than technique or cultural significance. Where does this leave cookbook authors? When did this shift from cultural documentation to content creation occur, and what have we lost? How has the rise of influencer culture and social media algorithms reshaped our understanding of culinary traditions? Are we witnessing the death of authentic culinary documentation, or is this an evolution? And lastly, how can we balance the need for accessible, marketable cookbooks with the responsibility to document vanishing food traditions? Despite the prominence of social media influencers sharing quick and easy recipes with shortcuts, erasing cultural context, and lacking historical narratives, there are an increasing number of conscious cookbook authors using social media to center the recording and preservation of living cultural practices.

Over the years, the study of cookbooks has proven fruitful in our understanding of people's changing relationships to food, their use as tools to learn how and what to cook, and their role in forming and transforming national cuisines (Goody, 1982; Mennell, 1996; Appadurai, 1988; Cusack, 2000; Humble, 2005; Symons, 2009; Gvion, 2009; Driver 2009; Floyd & Foster, 2010; cited in Crowther, 2018). Often regarded as practical literature of advanced civilisations, Cookbooks reveal unique cultural narratives. They merge the functional utility of manuals with the sensory allure of literary expression, reflecting changes in dietary norms, culinary practices, meal structures, economic considerations, market fluctuations, and domestic ideologies (Appadurai,1988:300). For a long time, the presence of cookbooks implied a certain level of literacy and often reflected the work of specialists seeking to standardise kitchen practices, preserve culinary knowledge, and promote specific traditions. In the post-Covid era, where existing practices and habits were tested, this changed with the consequence of social media on contemporary recipe writing. A recent article in the Independent discussing the evolving landscape of cookbook publishing highlighted the significant influence of social media on contemporary recipe writing, claiming that digital platforms have democratised the field and can co-exist alongside cookbooks, allowing more unknown home cooks and food enthusiasts to share their culinary creations with a broad audience (Salter:2024). Whilst this may be true, there are numerous scholars, including Pollan (2009) and Jaffe and Gertler (2006), argue that growing reliance on gadgets, processed and ready-made foods, domestic technologies, and food media have transformed or even undermined traditional cooking skills, gender relations, eating patterns, and forms of knowledge transmission.

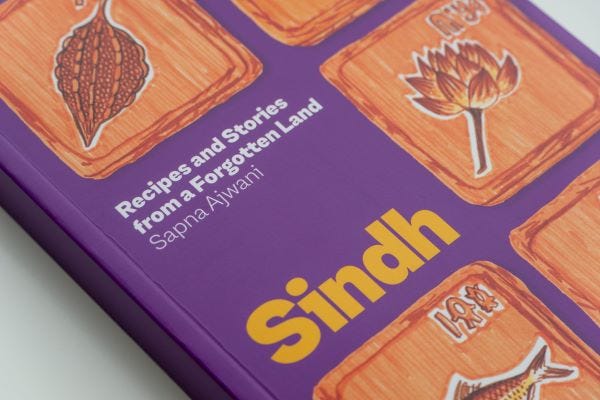

In the first term of our Food Forum Seminar' 24/'25 at SOAS, we had the chance to listen to three cookbook authors coming from different cultural, socio-economic, and career backgrounds but with one common denominator: the desire to share recipes, histories, and long-lost techniques of non-Western regions in an accessible manner. The speaker that caught my attention was Sapna Ajwani, the cookbook author of Sindh: Sindhi Recipes and Stories from a Forgotten Land. Born in Mumbai to a Sindhi family that fled their land after Partition in 1947, she spoke the language and learned about traditional arts and foods. It was fascinating to hear her talk about her motive behind the cookbook and how she started hosting supper clubs and cooking traditional Sindhi recipes, primarily because I had not heard much about the region or the origin of the word "Sindh." Most of Ajwani’s friends who tried her food would comment how different it was from what they ate at an Indian restaurant in London, and Ajwani would respond by saying, "Obviously, it is Sindhi food; there are no restaurants." Ajwani started her supper club, Sindhi Gusto, in 2016, allowing diners to explore her native flavors and learn more about the culture. In her presentation, she mentioned that in the supper clubs, she usually begins with an introduction tracing the history of Sindh from the time of the Indus Valley civilisation 7000 years ago, traveling back in time until today, highlighting what the Partition of 1947 did to Sindh people and how it created a division. Her research for the book started in 2019, and she traveled there to understand what Pakistani Sindh people eat (2020).

The passion of Ajwani, wanting to share Sindhi food and culture, her story, and her career path of shifting from an investment banker to a cookbook author, made me hopeful for the future. In this context, I found her role similar to that of an anthropologist or a historian, with her drive to shed light on forgotten culinary traditions, research historical documents, including maps, and conduct interviews with other Sindhi people to share their recipes. Cookbook authors can often uncover forgotten traditions, such as the preservation of food, connecting them to broader historical narratives. In this case, investigating how certain ingredients or techniques fell out of favour due to colonial powers, migration patterns, or social movements in the region that happened over time provides valuable insights into cultural evolution. What struck me was her socioeconomic and cultural positioning within the Western context of living in the diaspora; "The audience, as well as the authors of the English-language cookbooks produced in India in the last two decades, are middle-class urban women" (Appadurai, 1988:5). I wondered if this statement changed over time and whether it applied to Indian cookbook writers living in diaspora as well.

Another speaker of the first term was a 4th-generation Singaporean Chinese pastry chef and author of Chinese Pastry School, Yeo Min. Min explained that her journey in the kitchen started as a necessity when she was an undergraduate student living in London; cooking in communal kitchens became a form of procrastination to avoid working on school projects. This inspired Min to switch to the food industry after working as a social worker for two years. In her presentation, she emphasised the loss of tradition and intergenerational passing of pastry recipes due to the closing of traditional pastry shops and the lack of cooking measurements. Compared to Ajwani's experience collecting recipes and data, Min stated that she found it challenging to get cooks from older generations (mostly grandmas) to share their recipes, as they were hesitant because they did not want to share them outside their families. However, Min was determined to keep the craft alive by recording traditional techniques and research, ensuring the book was a resource for readers and providing context instead of short video posts on social media. She emphasised that there is a fine line between innovation and culinary appropriation, and that context and principles were important. I agree. As a passionate amateur cook and food lover, I appreciate technological appliances that save time and effort, although I respect traditional recipes and using passed-on family cookbooks.

In New York Times, Pollan critically analyses the transformation of cooking culture in American society (or the West in general), focusing on the shift from hands-on food preparation to passive food consumption and food as entertainment. Drawing on anthropological theory, particularly research by Claude Lévi-Strauss and Richard Wrangham, he positions cooking as a fundamental human activity that shaped our evolution and social development. This framework emphasises the cultural significance of cooking skills beyond mere sustenance. Pollan further argues that the loss of cooking skills represents more than just a change in food preparation methods; it signifies a fundamental shift in how we relate to food, family, and cultural transmission. How does the loss of cooking skills and the evolution of cooking appliances affect cookbook writing in the 21st century? Do more cookbook authors give in to trends and try to simplify recipes by diminishing heritage knowledge and cultural traditions?

The evolution of cooking skills and kitchen technology has profoundly impacted cookbook writing in the 21st century, creating a complex tension between the preservation of cultural knowledge and adaptation to modern lifestyles. The rise of convenience-oriented cooking appliances and the decline in traditional cooking skills has led many cookbook authors to adapt their approach, often simplifying recipes and techniques to accommodate modern kitchen practices. Sitting in the comfort of my mother-in-law's home in Leeds, where she carefully reads over her cookbook recipes and goes over her measurements whilst using her AGA, I find the famous British cookery writer Beverly Jarvis's confession on how she will use five air fryers for cooking a festive feast this year quite amusing. Contemporary cookbook writing often reflects a fundamental restructuring of how culinary knowledge is transmitted, frequently emphasising speed and accessibility over depth of cultural understanding. This shift parallels what anthropologist Jack Goody (1982) identified as the transformation of cooking from a culturally embedded practice to a commodified activity. The market pressures of publishing in the digital age have further complicated this dynamic. Cookbook authors face increasing pressure to create content that aligns with social media trends and modern cooking shows, potentially at the expense of preserving traditional knowledge.

Looking forward, cookbook authors will face the challenge of balancing accessibility with authenticity and technological adaptation with cultural preservation. The most successful modern cookbook authors may be those who can bridge this gap, providing practical, technology-friendly instructions while maintaining the cultural context and traditional knowledge that give cooking its deeper meaning. The question remains whether future generations of cookbook authors will continue to find ways to preserve and transmit traditional culinary knowledge while adapting to evolving technological and social landscapes. What do you think?

If you have been enjoying my Substack please spread the word with loved ones and people who might enjoy reading it too!