Leftovers of Memory

Cooking, Waste, and Care in Greece and Beyond

Food waste is one of the most urgent yet paradoxical global challenges we face today. Despite technological advances in food production and distribution, vast quantities of edible food are discarded daily, even as global hunger persists. According to the Food & Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, approximately 14 percent of the world's food, valued at $400 billion, is lost annually between harvest and the retail market (FAO, 2019). Across different social and cultural contexts, many scholars and practitioners have explored how embodied culinary knowledge can counter the systemic causes of food waste. Having lived alone in London for over 15 years now, I am very conscious of wasting food or having any leftovers whilst cooking, but regardless, I have been wasteful on more occasions than I would have wanted. Growing up in a Turkish household with Pontus Greek and Albanian Heritage, I was encouraged to finish what was left on my plate and not take more than I could eat, so when I came to London to study, I was shocked to see how much food was wasted in restaurants and in general in larger supermarket chains. Recent findings show that restaurants and food service establishments in the UK generate around 1 million tonnes of food waste annually. Inspired by Dr Nafsika Papacharalampous's Food Forum presentation on the 23rd of February 2025 at SOAS, titled Eating Fish Heads and Lamb Hearts: Ethnographic Reflections on Sustainability and Food Waste in Greece, I aim to write a comparative text exploring how memory, skills, and cultural Heritage shape food waste in Greece but also beyond in the context of my own experience living in London and having volunteered in a charity that feeds vulnerable people and works with excess food waste. By implementing ethnographic insight, personal experience, and anthropological theory, I aim to focus on both Papacharalampous' research in comparison to David E. Sutton's book Secrets from the Greek Kitchen (2014) by linking them to contemporary urban food activism against waste, with particular reference to Refettorio Felix in London, which I engaged with during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this blog post, I argue that the intersection of traditional culinary practices and contemporary urban activism offers valuable insights into reducing food waste. However, they operate through different mechanisms: one through the embodied transmission of memory and resourceful skill and the other through conscious ethical interventions within capitalist infrastructures. Through this comparative analysis, I will assess how these approaches complement and challenge each other and explore how combining them might inform more resilient and ethical food systems today.

When we had the Zoom presentation from Papacharalampous, who describes herself as a Food Anthropologist, teacher, researcher, and culinary curator and holds a PhD from SOAS, I was immediately drawn to her thorough research methodologies and multidisciplinary approach. Before writing her book The Metamorphosis of Greek Cuisine (2024), Papacharalampous started her fieldwork in Athens in 2013. She had years of research and findings building on her ethnography of deli foods, restaurant smells, and foodways of crisis (especially the economic turmoil of the 2010s). In anthropological discussions of food, memory, and material practice, Dr. Nafsika Papacharalampous's works and David Sutton's offer significant observation and understanding of how cooking skills and culinary memory interact with attitudes toward food waste in Greece. How does the erosion of embodied culinary knowledge contribute to food waste in contemporary societies? Can remembering and reviving traditional cooking practices meaningfully challenge the systemic causes of food waste today? How did conventional Greek cooking skills, shaped by histories of scarcity and frugality, offer a form of resilience during economic and social crises? What lessons can be drawn from Greek culinary traditions for rethinking food sustainability and dignity in urban, capitalist societies? Finally, if waste is a cultural choice, what kinds of new ethical frameworks around food might emerge from combining traditional knowledge with contemporary urban activism? Although each scholar brings a unique perspective to these questions, their research shares a critical common ground: both approach food practices as repositories of collective and personal memory, emphasising the embodied, often non-verbal transmission of knowledge that inherently counters wastefulness.

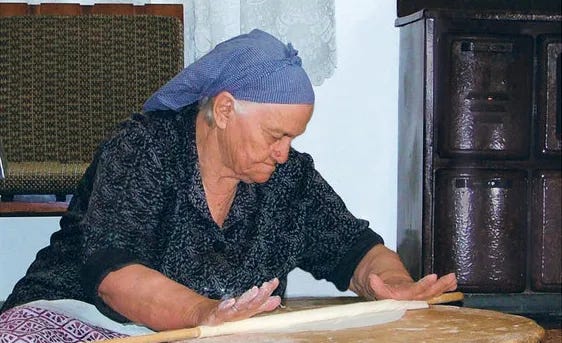

Sutton (2001) explores how food serves as a medium for memory, particularly through sensory experiences like taste and smell. His ethnographic work on the Greek island of Kalymnos illustrates that culinary practices are deeply intertwined with memory, not just through recipes but through the embodied act of cooking and eating. Sutton argues that memory is reproduced through the repeated handling of ingredients, intuitive recipe adjustments, and resourcefully managing scarcity. These practices are often transmitted through sensory modalities rather than purely linguistic means. For instance, Sutton notes that Kalymnians plan in the present to remember food events in the future, a concept he refers to as "prospective memory" (Sutton, 2001, p. 19). He also discusses how food is linked to various cycles depending on agriculture, male migration, and religion, which aid in remembering the past (Sutton, 2001, pp. 28–29). Papacharalampous' research into foodways in contemporary Athens, particularly during and after the Greek financial crisis, highlights how culinary memory and practical skills mediate responses to food insecurity and waste. In her work on Urban Culinary Traditions in Athens: Memory, Crisis, and Sustainability (2021), she demonstrates that culinary repertoires inherited from older generations emphasise frugality, improvisation, and the full use of ingredients.

Like Sutton, Papacharalampous stresses the tacit dimension of these skills: they are learned through doing, not merely through codified instruction. In this context, knowledge about how to repurpose leftovers or creatively adapt to what is available becomes a form of resilience and an ethical stance toward food. In her presentation, Papacharalampous emphasised that more food is wasted in the industrialised world than in developing countries and that in medium to high-income countries, food waste typically occurs at the end of the supply chain while still suitable for human consumption. She then linked the behaviours around food in Greece to binaries such as "Food is clean, waste is dirty, food is safe, waste is dangerous; food is associated with taste and quality…" (Food Forum, 2025). The binaries through which we conceptualise food, such as "fresh" vs. "stale," "clean" vs. "dirty," and "edible" vs. "inedible," play a decisive role in shaping our attitudes toward consumption and, crucially, food waste. These oppositions are not universal or fixed but culturally constructed categories that reflect broader social, economic, and moral worldviews. As such, they influence what we eat, what we discard, and how we feel about that act of discarding. In different cultural contexts, these binaries are produced, negotiated, and sometimes subverted in ways that significantly impact the scale and nature of food waste.

As an independent curator and anthropology of food student living alone in London during the pandemic, my voluntary work at Refettorio Felix between Summer 2020 and Winter 2022 gave me a uniquely embodied perspective on the intersections between food waste, community, and care. Refettorio Felix, based in Earl's Court, operates as a community kitchen and a therapeutic centre. Founded in 2017 through a collaboration between St Cuthbert's Centre, Chef Massimo Bottura's Food for Soul initiative, and The Felix Project, the charity reimagines food waste as an opportunity for nourishment and dignity. By rescuing surplus food with produce deemed imperfect by supermarkets, food suppliers, and farms, they create restaurant-quality meals for vulnerable people experiencing homelessness, poverty, and mental health challenges (Refettorio Felix, 2025). Globally, COVID-19 profoundly reshaped the dynamics of food production, distribution, and consumption, whereas, in London, the crisis exposed the vulnerabilities of a system characterised by overproduction, just-in-time logistics, and rampant consumer waste. Amid these upheavals, charities like Refettorio Felix emerged as vital actors in mitigating both food waste and social isolation. During my time at Refettorio Felix, the kitchen operated under extraordinary conditions: city-wide lockdowns, disrupted food supply chains, and a surge in vulnerable populations needing assistance. I remember that we had to regularly sanitize, test and keep our social distance. Each day, the charity received unpredictable donations of surplus food, including boxes of overripe fruits, misshapen vegetables, and expired canned goods, requiring the kitchen team to improvise menus with speed, creativity, and care. This practice of "making do," of creatively repurposing whatever was available, resonates strongly with what Papacharalampous (2025 & 2019) describes in her study of Athenian households during the Greek financial crisis: an embodied culinary adaptability, deeply rooted in inherited practices, where waste was minimised through improvisation, sensory knowledge, and frugality.

In Greece, food is not just a material object to be consumed or discarded but a medium through which social relations, family histories, and moral values are enacted. The Greek way of living and eating strongly emphasises home cooking, seasonality, and the respectful handling of ingredients. Meals are often shared communally, and cooking is typically guided by inherited knowledge passed down through generations. This embodied knowledge encourages the intuitive use of leftovers, creative adaptation to what is available, and a deep moral aversion to waste. Sutton (2014:13,14), in his ethnography of Kalymnos, highlights how cooking in Greek households is often guided by sensory perception such as smell, taste, and touch rather than strict recipes, allowing cooks to improvise and adapt to their resources, thus minimising waste. Papacharalampous (2019) further explores how these cultural practices persisted and intensified during the Greek financial crisis. In urban Athenian households, families leaned on traditional culinary repertoires to navigate new forms of precarity. Improvised dishes from scraps, practices like freezing or reusing oil, and stretching meals to last over several days were not just survival strategies but deeply cultural acts that connected individuals to a more extended history of food scarcity and resilience. The act of not wasting food became a way of asserting dignity and continuity in the face of economic rupture. Cultural factors also shape perceptions of what counts as waste. In Greece, for instance, the concept of "leftovers" often carries less stigma than in Anglo-Western contexts. Dishes such as revithada (chickpea stew) or fakes(lentil soup) are designed to improve with time, blurring the boundary between "fresh" and "reheated." These attitudes reflect a broader Mediterranean ethic of continuity and transformation in food use—values that directly counter the disposable culture in many industrialized nations. This also resonates with Mary Douglas's (1966) idea that dirt (or waste) is "matter out of place"; what one culture discards, another may transform. Cultural practices in Greece often imbue food with a moral quality. The concept of filoxenia (hospitality) requires the host to offer food generously, and wasting food can be seen as disrespectful to the guest and the food itself. In many rural areas, even today, practices such as feeding animals with kitchen scraps, composting, or turning old bread into paximadi (rusk) reflect a circular relationship with practical and culturally embedded food.

David Sutton's conceptualisation of memory and skill finds echoes in the Refettorio Felix kitchen where he observes, much of culinary practice is learned not through formal instruction but through sensory engagement: the feel of dough under the fingers, the smell of a sauce at different stages of cooking, the intuitive adjustments made when ingredients are missing (Sutton, 2014: 14 & 27). At Refettorio Felix, I experienced this firsthand. Recipes were flexible guidelines rather than fixed instructions; the chefs encouraged volunteers to trust their senses, to taste, to adjust, and to be guided by the materiality of the food itself. Cooking became an act of relational knowledge, as volunteers shared tips, memories, and techniques from diverse cultural backgrounds, mirroring Sutton’s description of how food binds memory, place, and identity.

Overall, both Papacharalampous and Sutton emphasise the socio-cultural dimensions of food practices, particularly in times of crisis. In Athens, Papacharalampous (2019) shows how frugal cooking was not merely an economic adaptation but also a means of maintaining social bonds, dignity, and identity amidst precarity. Similarly, Refettorio Felix was not only about feeding bodies but also about restoring a sense of belonging and worth. Every plate served carried an ethical commitment to care: meals were plated thoughtfully, tables were set with dignity, and service was performed with warmth, reflecting the charity’s philosophy that food is about more than nutrition—it is about social repair. My experience thus highlighted, in real time, the anthropological insights that Papacharalampous and Sutton theorise. It illustrated how culinary practices, shaped by memory, skill, and material constraints, are central to human resilience. Furthermore, it confirmed that food waste is as much a cultural and ethical problem as it is an economic or logistical one. Without the embodied skills to improvise, preserve, and adapt, as Papacharalampous found in Athens and Sutton in Kalymnos, surplus food is easily wasted. Therefore, Greek culinary traditions illustrate that food waste is not inevitable but the outcome of particular social and economic structures. Thinking of the intersection of my interests in Anthropology, food and art, in the context of leftovers the artist Maisie Cousins’ stiriking modern interpretation of still life photographs come to mind. I cannot help but think about the fine line between disgust and seduction. The subject matter in her images, some of which are still very much alive, are part of a flamboyant, opulent and at first glance sensual mise-en-scène.

Reflecting back on my volunteering experience also sharpened my critical understanding of the contradictions within capitalist food systems, a theme implicitly present in both scholars’ works. The surplus food we received daily at Refettorio Felix was a material testament to the excesses and inequalities of the supply chain: edible food discarded at massive scales even as hunger grew. By transforming this waste into nourishment, we participated, however modestly, in an ethic of remembering and restoring, standing in stark contrast to the forgetfulness and disposability promoted by industrial food capitalism. In conclusion, my lived experience at Refettorio Felix served as a powerful, embodied extension of the theoretical frameworks developed by Papacharalampous and Sutton. It indicated how the embodied knowledge of cooking, memory, and care are not only anthropological concepts but urgent, vital practices that can transform food waste into sustenance, and crisis into community.

References

Counihan, C. (2016) A Tortilla Is Like Life: Food and Culture in the San Luis Valley of Colorado. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Evans, D. (2014) Food Waste: Home Consumption, Material Culture and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Fenton, A. (2011) Food and Farming in Scotland, 1200–2000: A History. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

“Food Loss and Waste.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://www.fao.org/nutrition/capacity-development/food-loss-and-waste/en/.

Papacharalampous, N. (2025), SOAS Food Studies Centre, Eating Fish Heads and Lamb Hearts: Ethnographic Reflections on Sustainability and Food Waste in Greece, Food Forum presentation.

Papacharalampous, N. (2019) The Metamorphosis of Greek Cuisine: Sociability, Precarity and Foodways of Crisis in Middle-Class Athens (PhD thesis). SOAS University of London. Available at: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32479/ (Accessed: 27 April 2025).

Papacharalampous, N. (2021) Urban Culinary Traditions in Athens: Memory, Crisis and Sustainability. In: T. Bottica and J. Klein, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Food History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Refettorio Felix. Accessed April 21, 2025. https://www.refettoriofelix.com/our-story.

Sutton, D. E. (2001) Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory. Oxford: Berg.

Sutton, D. E. (2014) Secrets from the Greek Kitchen: Cooking, Skill, and Everyday Life on an Aegean Island. Berkeley: University of California Press.

WRAP (2020) COVID-19: Impact on Food Waste Behaviour. Banbury: WRAP. Available at: https://wrap.org.uk/resources/report/covid-19-impact-food-waste-behaviour (Accessed: 27 April 2025).